Peering into Yugoslavian Punk & New Wave

Text:

Ian Martin

Image:

Courtesy of Matija Praznik

Issue:

Fall-Winter 2014-15

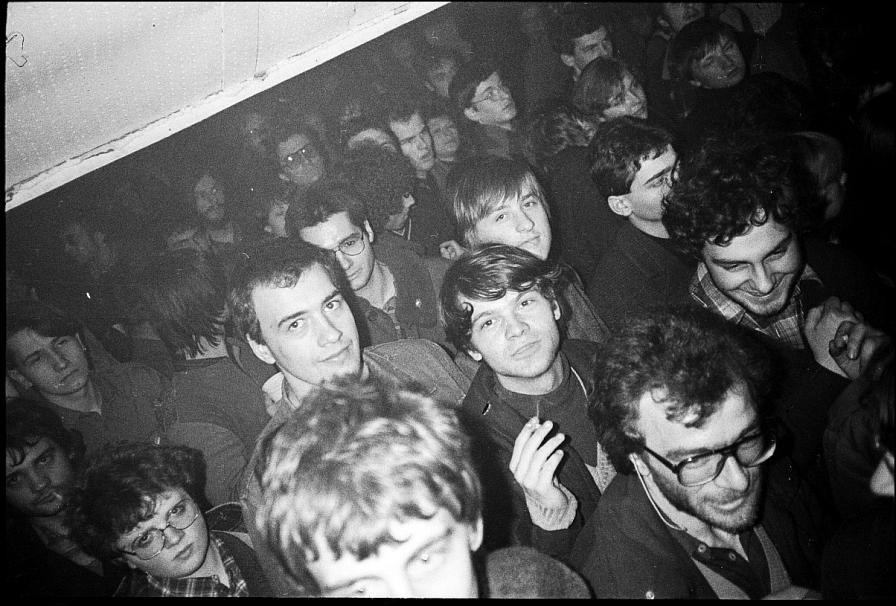

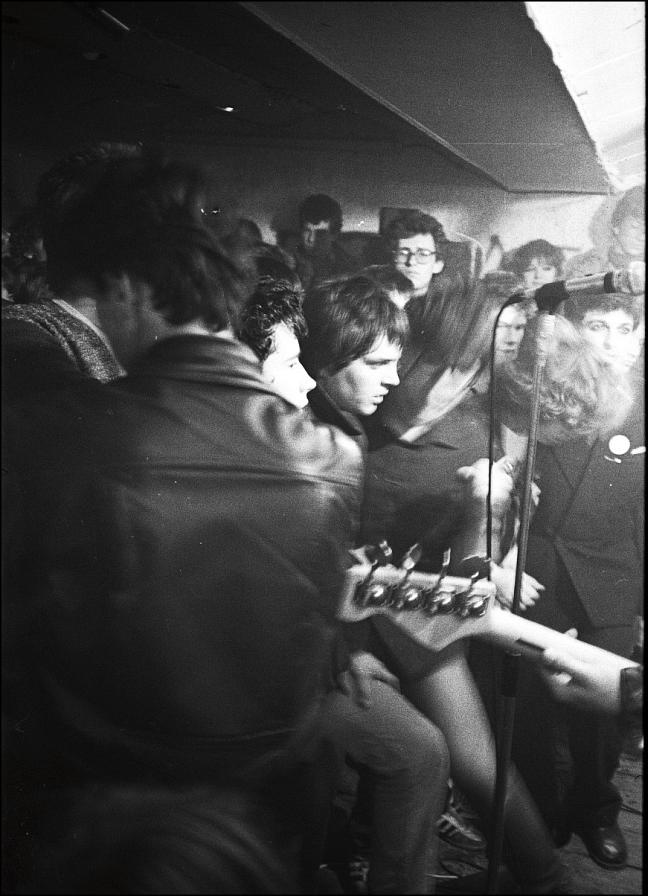

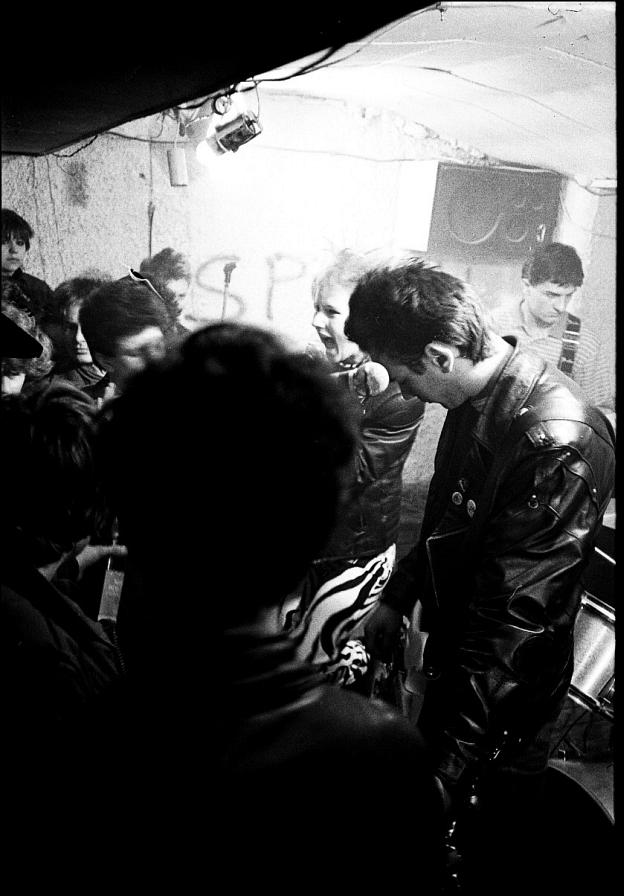

A look into the revolutionary potential in the Yugoslavian punk and new wave underground.

On an icy December night in 2012, a crowd of people gather around a Christmas tree at an outdoor stage in the center of Slovenia’s capital city, Ljubljana. In front of the Ljubljana Plečnik Market, the revelers are not there to sing carols though. The city is tense after violence has erupted during recent demonstrations against Slovenia’s reactionary Prime Minister Janez Janša, and amid fears of overzealous police and suspicions of agents provocateur. These people have gathered in both celebration and protest. In response to an ill-advised tweet from Janša that the groundswell of public anger against him and his Slovenian Democratic Party government was akin to a “zombie uprising,” many participants in this “Protestival” have daubed themselves with zombie make-up, and musicians are performing on the stage beneath a giant, looming skeletal figure held aloft by puppeteers. An acoustic guitar strikes up and a man sings: “The lighthouse of the century, shines only in one direction, Just towards the rich, so as not to cause trouble, Let the fleet of tycoons, sail without worries, Even if the boat is rotting, what matters is that it shines.” Wind back to the late 1970s and this band, Buldogi (The Bulldogs), at the age of only fourteen years, were inspired to form and ended up becoming part of one of the most vibrant punk and new wave scenes in the world: in the unlikely environment of the Socialist Federative Republic of Yugoslavia. Kept separate from the Soviet bloc by iconic revolutionary leader Josip Broz Tito, Yugoslavia had forged a position for itself as a founding member of the “non-aligned movement” of nations who rejected the influence of both America and the USSR. While Yugoslavians enjoyed a greater degree of freedom and closer connections to the West than most fellow communist countries, Tito’s state was no liberal democracy and political and cultural life were restricted in a number of ways. The 1960s student movement had been fairly comprehensively suppressed in the early 1970s and music was largely apolitical throughout much of the ‘60s and ‘70s, ranging from inoffensive pop to progressive rock and avant-jazz. Live music events operated under numerous restrictions, including stipulations that concerts keep the house lights on throughout performances and audiences remained seated at all times.

However, the desiccated and never really musically inclined in the first place student movement left in place certain infrastructure that would later be instrumental in the development of punk, including various student newspapers such as Tribuna and Mladina, and most importantly Ljubljana radio station Radio Student. A key figure at Radio Student in the late ‘70s was

However, the desiccated and never really musically inclined in the first place student movement left in place certain infrastructure that would later be instrumental in the development of punk, including various student newspapers such as Tribuna and Mladina, and most importantly Ljubljana radio station Radio Student. A key figure at Radio Student in the late ‘70s was

You have read a selection from Issue 1: Fall-Winter 2014. To read this text in full, purchase a limited-edition print issue in our store for $12.00 (+ shipping) or visit one of our stockists in person, or download our free reader-style app from the Apple App store or Google Play store to purchase a digital edition to read on your smartphone or tablet for $5.00.